The Sharp Gentleman Guide to Drinking Scotch Whisky

In the history of manliness, no other drink has ever commanded such presence, machismo, character, or class. Single-malt whisky from Scotland (the very definition of Scotch) packs a punch that is delicious to some and displeasing to others, but is undeniably known as the manliest of all liquors.

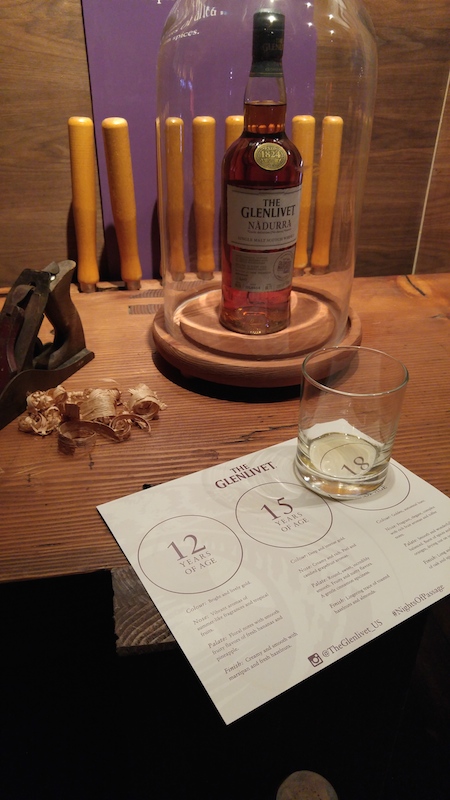

I was recently invited to the Guardians of the Glenlivet presentation when they came through Dallas. I was already a Guardian, but who am I to turn down free whisky and conversation? As a man that enjoys his Scotch, I feel that Glenlivet does a lot of things right when it comes to flavor, finish, and finances. It’s not too expensive, but drinks like much higher-end single malts, which makes it accessible to more gentlemen.

What I learned (again) that night, was how little most people knew about Scotch, and its cousin, Bourbon Whiskey. When choosing a single-malt, what should you look for? Does price matter? Does age matter? Does oak matter? What the hell is a dram?

The best place to start is at the beginning, right? Here’s a crash course guide to drinking scotch whisky:

What’s a Dram Anyway?

The definition has changed slightly over time, but a dram is essentially an ounce in a glass. It is not a shot. You do not shoot Scotch. Ever. When you ask for a dram of Whisky, you will most likely get about an ounce of it in a a tumbler or Glencairn glass. Technically, a dram is about a teaspoon, or a little more than an eighth of an ounce, but time has seen the amount relax and become an ounce casually. Before we jump into how you should properly drink it, let’s touch on what creates the flavor and finish.

The definition has changed slightly over time, but a dram is essentially an ounce in a glass. It is not a shot. You do not shoot Scotch. Ever. When you ask for a dram of Whisky, you will most likely get about an ounce of it in a a tumbler or Glencairn glass. Technically, a dram is about a teaspoon, or a little more than an eighth of an ounce, but time has seen the amount relax and become an ounce casually. Before we jump into how you should properly drink it, let’s touch on what creates the flavor and finish.

Finished in Scotland

For a whisky to be considered Scotch, it must be aged in Scotland for a minimum of three years. Each whisky reaches its maturation at different ages, and most are now aged anywhere from 8-20 years. Depending on the age and the type of wood in which the whisky was barreled, different styles, colors, and finishes can be created from the same distilled alcohol. Many find that the longer the whisky is aged, the smoother it becomes. Another perspective sees the longer aging process as a better, more refined Scotch, and this makes the retail price significantly higher. We’ll talk about that in a minute…

Whisky vs. Whiskey

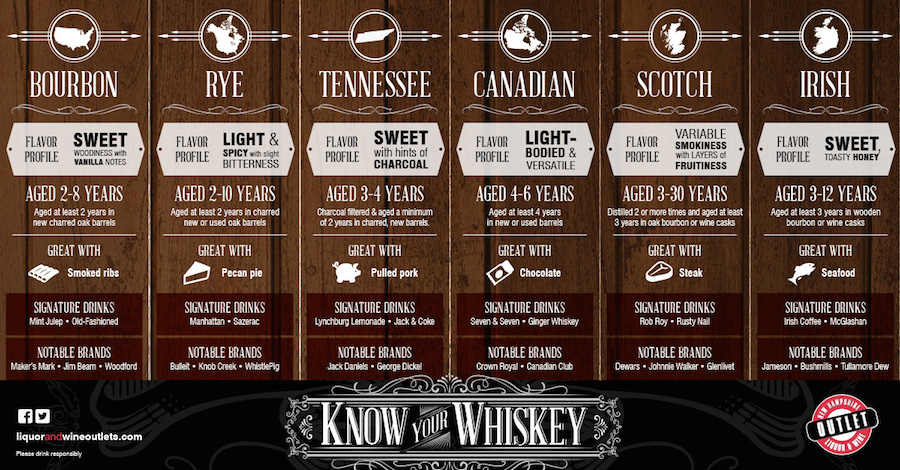

The Scots spell it whisky and the Irish spell it whiskey – with an extra e. The difference in spelling comes from the translations of the word usquebaugh from the Scottish and Irish Gaelic forms. It means water of life in both languages, but the Irish added an ‘e’ while the Scots did not. Whiskey with the extra ‘e’ is also used when referring to American whiskies across the pond. Now you know!

Scotch Distilleries & Regions

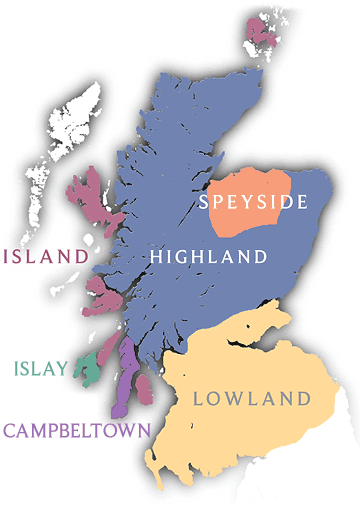

There are five primary regions for distilling whisky in Scotland, and they differ in the same way that wines differ in flavor depending on their origin. The same way a wine from Napa Valley will be different than one from Bordeaux, France or Argentina, the origin of your whisky will carry its own distinct flavor and finish. The five regions are Lowland, Highland (includes Island), Speyside, Islay, and Campbeltown.

There are five primary regions for distilling whisky in Scotland, and they differ in the same way that wines differ in flavor depending on their origin. The same way a wine from Napa Valley will be different than one from Bordeaux, France or Argentina, the origin of your whisky will carry its own distinct flavor and finish. The five regions are Lowland, Highland (includes Island), Speyside, Islay, and Campbeltown.

- Lowland — many find this region offers the more milder and smoother options. Having a little more mellowed-out finish makes this a great Scotch for beginners. Three distilleries in operation include: Glenkinchie, Bladnoch, and Auchentoshan.

- Highland — this is the largest geographic region for distilleries, and includes well-known names like: Glenmorangie, Dalmore, Talisker, and Dalwhinnie.

- Speyside — next to the River Spey, this area is home to the largest number of distilleries like: Glenfiddich, Aberlour, The Glenlivet, and The Macallan.

- Islay — known for heavier, more smoky/peaty Scotch varieties, this region has eight distilleries including: Ardbeg, Bowmore, and Laphroaig.

- Campbeltown — this is the smallest of the regions, and while it was once home to several distilleries, only three remain today: Glengyle, Glen Scotia, and Springbank.

You can get a much more complete map of the regions and all the distilleries in each by checking out this interactive map.

Making & Barreling Scotch Whisky

The different variations in flavors, finishes, and colors stems primarily from the barreling process. The underlying notes of peat, smoke, flowers, and spices like clove and cinnamon are all part of the malting process, but the whisky gains its color and finish from the wood used in barreling. Unfinished Scotch (freshly distilled) is placed in oak barrels, sometimes referred to as casks, to finish out the maturation process.

The different variations in flavors, finishes, and colors stems primarily from the barreling process. The underlying notes of peat, smoke, flowers, and spices like clove and cinnamon are all part of the malting process, but the whisky gains its color and finish from the wood used in barreling. Unfinished Scotch (freshly distilled) is placed in oak barrels, sometimes referred to as casks, to finish out the maturation process.

The process softens the whisky to mellow out the alcohol and introduce new flavors. Over time, the Scotch begins to retain the golden color of the interior finish of its barrel. A lot of distilleries make use of the traditional dry sherry barrels to finish their whisky, but some take it a step further and modify the barrel choice depending on the finishing age.

At the Glenlivet, for example, the 12 and 18-year single-malts are aged in traditional sherry oak, which gives them their sweet and spicy color and flavor. The 15-year, however, is aged in French Limousine Oak, traditionally used for Cognac, which gives the 15-year a distinctly smoother finish. Of the standard Glenlivet offerings, this one is my favorite. I haven’t tried the Nádurra selections yet, but when I do I’ll make sure to post a review.

How to Properly Drink Scotch Whisky

Now that you’ve got some understanding of Scotch, it’s time to delve into the proper way to drink it. While there are few rules to follow, two remain unbreakable:

Now that you’ve got some understanding of Scotch, it’s time to delve into the proper way to drink it. While there are few rules to follow, two remain unbreakable:

- You do not order a “shot of Scotch” and pound it at the bar. Ever.

- You do not use Scotch as a mixer. Blended whiskies, perhaps, but never the good stuff.

Now, the general rule about ice and water is brought up a lot. The rule dictates that you don’t add ice to your whisky because it shuts down the flavors and robs you of the full experience. Instead, you are invited to add a splash of water to your dram. This really opens up the floral notes and flavors of the whisky, and you’ll notice a difference immediately. The whisky is relaxed yet vibrant.

Personally, I don’t mind the ice rule. If you’re new to whisky, ice is probably your best friend. Many first-timers simply can’t stand the hit to the palette that whisky delivers, and a little ice helps to cool things off. My advice is to start with a single cube of ice in your dram and work your way to just a splash of room temperature water down the road.

Age – Price – Flavor

These are the next three categories of questions most people have regarding Scotch. What’s the best age? How much should I realistically spend on a bottle, and what region offers the best flavor? These questions are difficult to answer because each one is fairly subjective, but here is my personal advice:

- Age is not as important as the oak used to finish the whisky. American whiskies, for example, use brand new charred oak barrels in their stills, and that’s what gives their bourbon such a sweet finish and dark color. Whether it’s aged for 5 years or 50, it will get its character from the oak. One man’s “sherry oak” 18-year may not be as rich as another man’s 12-year aged in cognac oak.

- Relatively good Scotch begins around $50 a bottle. There are some that are slightly cheaper, but anything less than $40 isn’t worth your time. Any Scotch over $100 needs to come with a very good backstory. Yes, they’re out there, but some of the best whisky on earth can be had for around $80, making these triple-digit bottles a little unnecessary if you ask me.

- The best flavor is the one you find most appealing. Seriously. I can’t answer that one. I like The Macallan 12, the Dalmore 15, and Laphroaig Quarter Cask, personally. I normally don’t like a lot of peat or smoke in my Scotch, but the Laphroaig (traditionally very peaty and smoky) is much smoother in the quarter cask blend. You have to try a couple from each region and decide for yourself.

The bottom line in enjoying Scotch is to try a few of them and experiment to find what you like best. My first bottle was the Glenlivet 12-year many moons ago. I wasn’t sold on Scotch just yet. The Macallan 12-year opened my senses a little more and I moved to Glenmorangie 10-year after that. I ventured to the Islay region and tasted the smoke and peat of Laphroaig, and wasn’t a fan (the quarter cask is more mellow). I got my hands on a bottle of Dalmore 15-year, and fell in love.

Here are some pictures from the Guardians of Glenlivet event in Dallas

There are still dozens of different malts and blends I have yet to enjoy. I invite you to get started on your own quest as well. I hope this guide to drinking Scotch whisky helped you make sense of the letters and numbers you see at the liquor store, and inspired you to try a dram for yourself.

What is your favorite whisky? Are you a fan of a particular distillery I missed? Leave a comment with your suggestions!